Intention

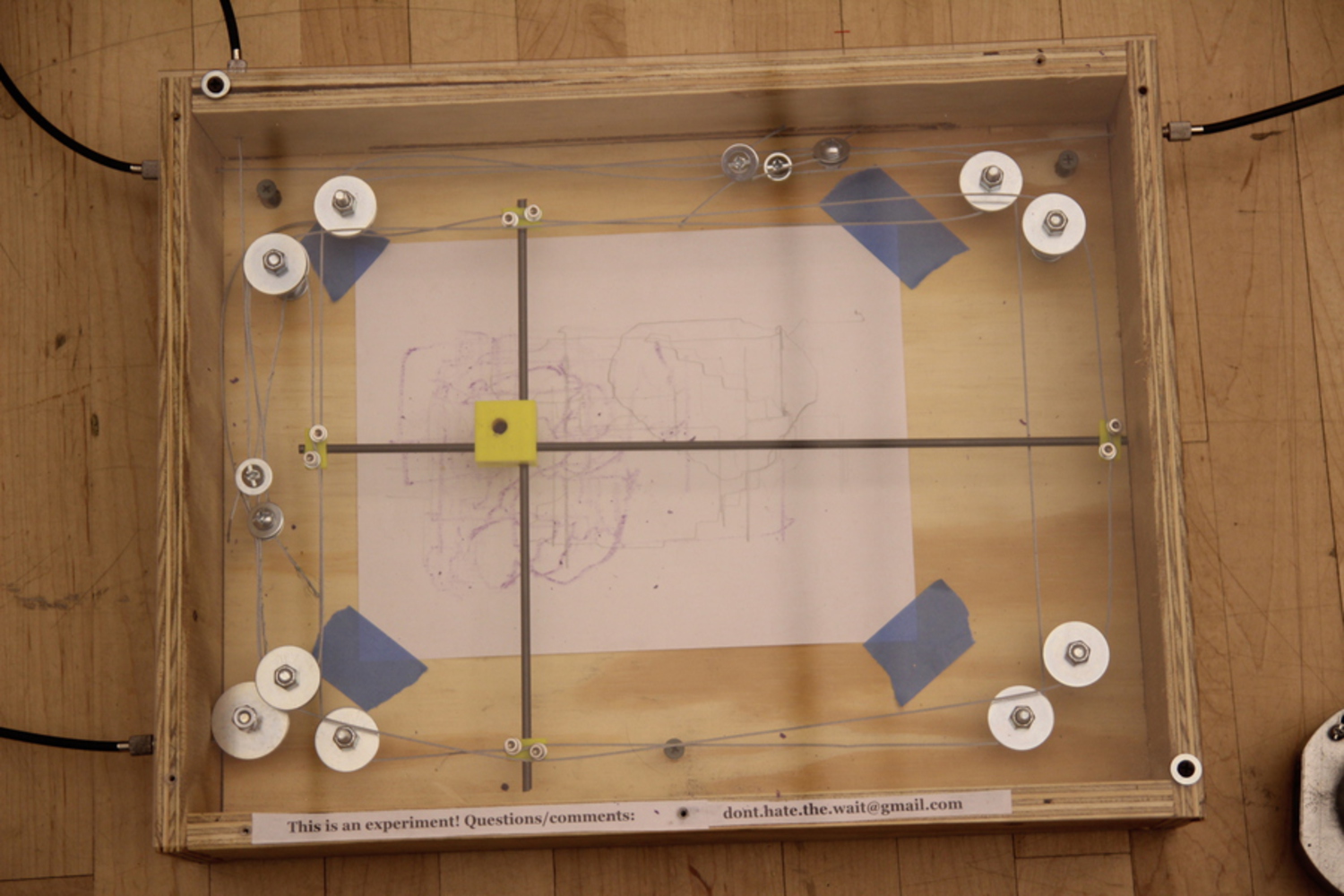

Start the Stop is intended to encourage strangers at a bus stop to interact with each other in the process of making art together. It is deliberately built with no instructions or obviously expressed expectations of the users, excepting arrows indicating that the control knobs should be turned but without any explanation of what might happen when one does that.People who are traveling around in public choose to not engage with strangers, probably often enough for very good reasons. However, the cumulative network effect of many socially disengaged people in the public sphere leads to a significant loss of connection, camaraderie, and humanity on the part of everyone. Intentional disengagement leads to a mitigation of effort and risk on a personal level (if you don't talk to a stranger they're less likely to be motivated to scream at you, etc.) but is a really large loss at a public level.

Start the Stop intends to give people entree to a simple, interesting, naturally engaging mode of interaction with strangers. It aims to bridge the self-enforced silence that dominates so many public spaces, using as its base case the archetypical locus of detached, alone-in-a-crowd waiting: the city bus stop.