Paul Klee would practice the violin in preparation to painting. His desire for expressive power can hardly be better found than in the wide-ranging, voluminous sound the instrument produces. What he called “warm up” I treat as direct influence, willingly or unwillingly finding its way into the visual outcome, or residue. Resultantly, the visual rhythm in Klee’s painting matches and conveys musical composition structures, but beyond the connection Klee’s mind claims, the relationship between the two remains unclear. In analyzing the association between musical piece and visual elements in painting, I seek to construct a translation mechanism between audible and visual form predicated on Klee’s artistic practice.

I decided to iterate the “warm up” assignment from our first class module where I created a piece of digital homage to a 20th century artist/artwork, in my case Paul Klee’s Insula Dulcamara. With this digital recreation as with my final project, an important consideration was to ask what “realm” the work I produced was in. Viewing reality as one of many and art as a window, Klee developed a “transcendentalist approach to the material world” as musician and painter.

It seems undeniable that there exists a link between music and visual form. This link for Klee constituted a duality rooted in Nature and the Cosmos. He believed, “Dualism should not be treated as a complimentary whole… Truth requires the consideration of all elements, the work of art — a fusion of them all.” To find and understand these elements, Klee stipulated the essential condition that the artist communicate with nature: “The artist is human; himself nature; part of nature within natural space.” This mindset led Klee to draw inspiration from both painting and music. “Senses of form and tone are of human primordial heritage. Klee fused both of these creative impulses into a new entity.”

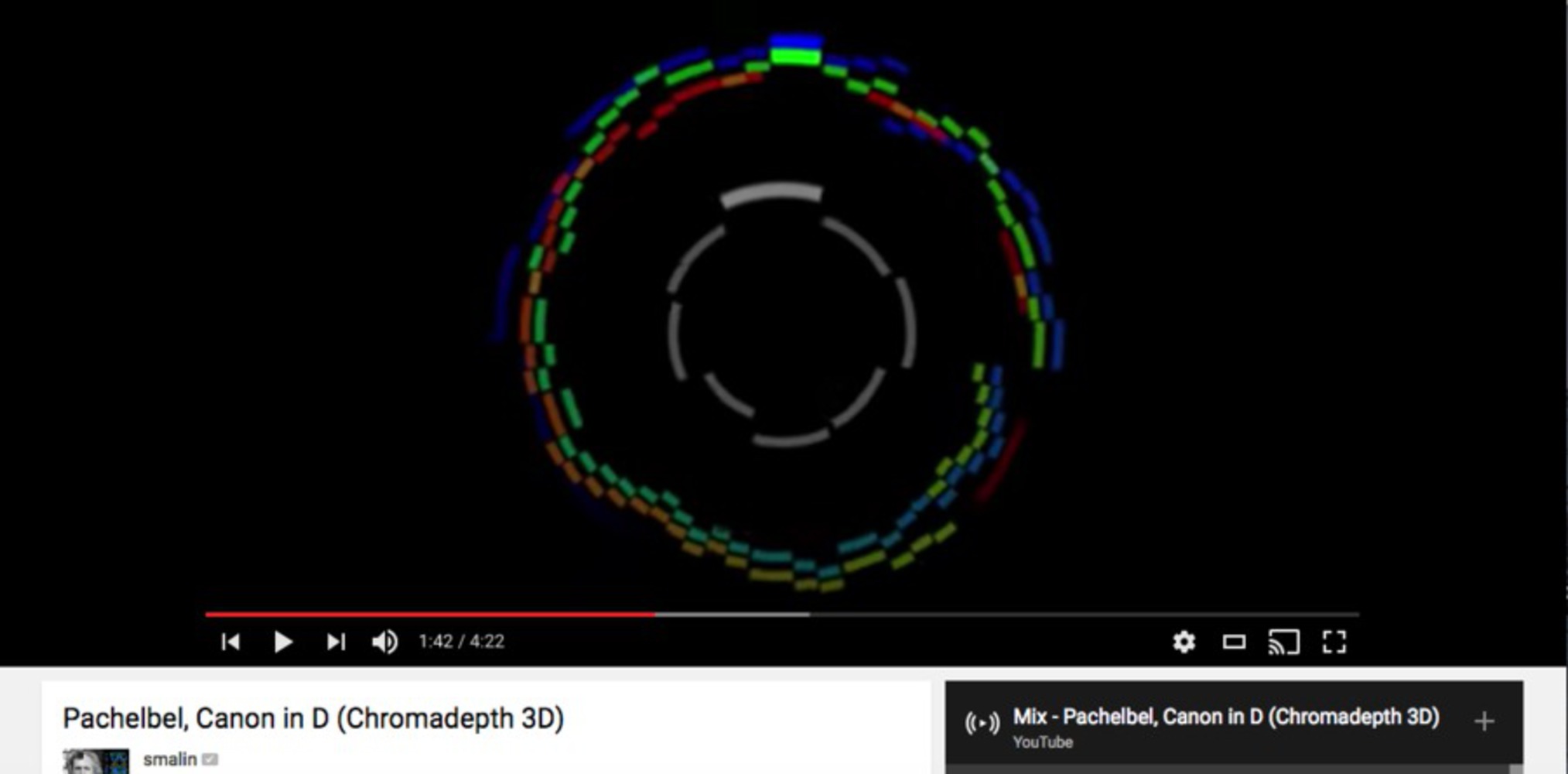

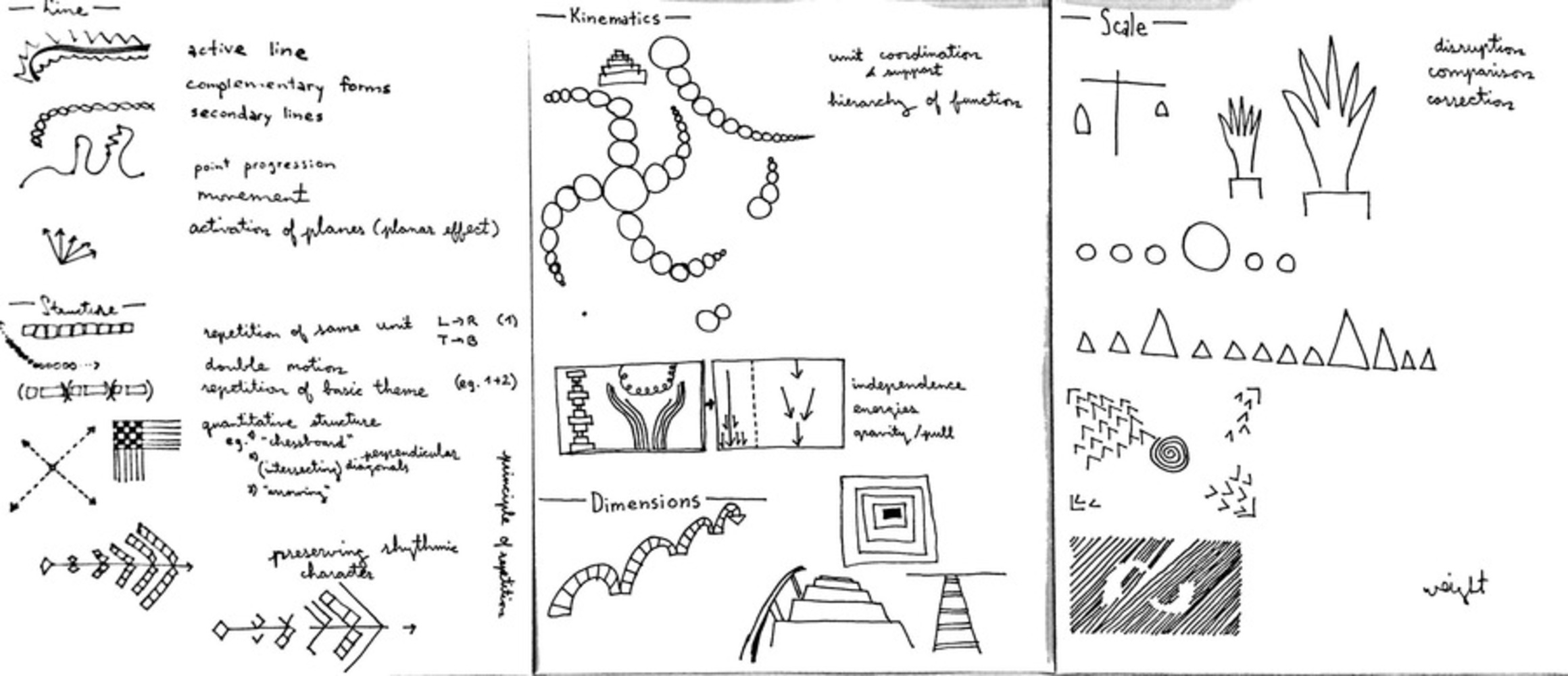

The “new entity” where creative impulses fused had been theoretically described by philosopher and social critic Theodore Adorno as the “point of convergence” between music and painting. Klee “visually revealed” this contact between the two art forms in his work with a focus on rhythm as the important link between music and painting. He saw rhythm as “capable of illustrating temporal movements in both” and in his early paintings attempted to "solve structural affinities between the two." Patrice Pavis noted that “Klee’s painting “plays simultaneously ‘on both panels’, visual and auditive, according to the two rhythms peculiar to each system.” Klee had linked painting and music through the course of his life, but what was the causal relationship between the two in his practice?

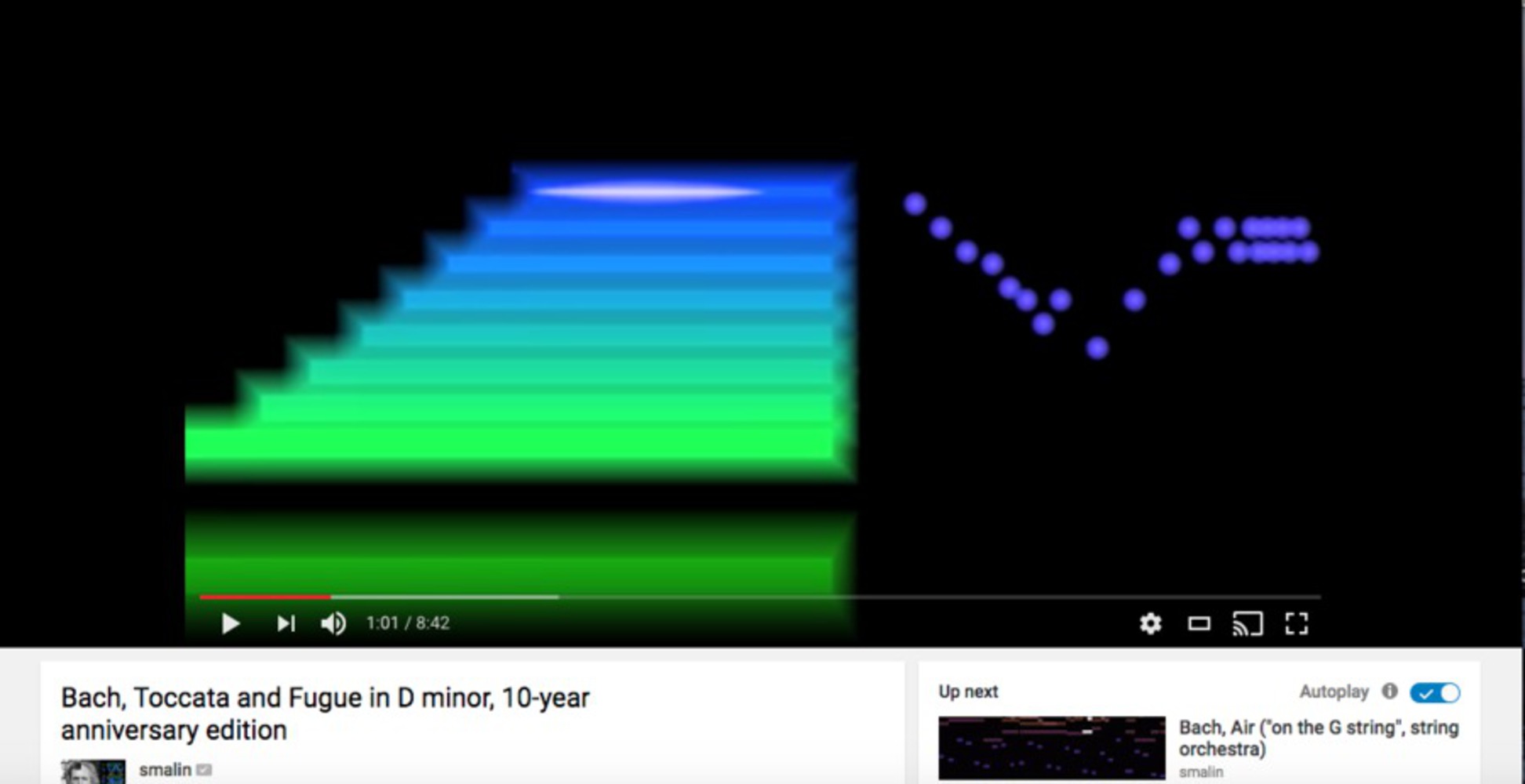

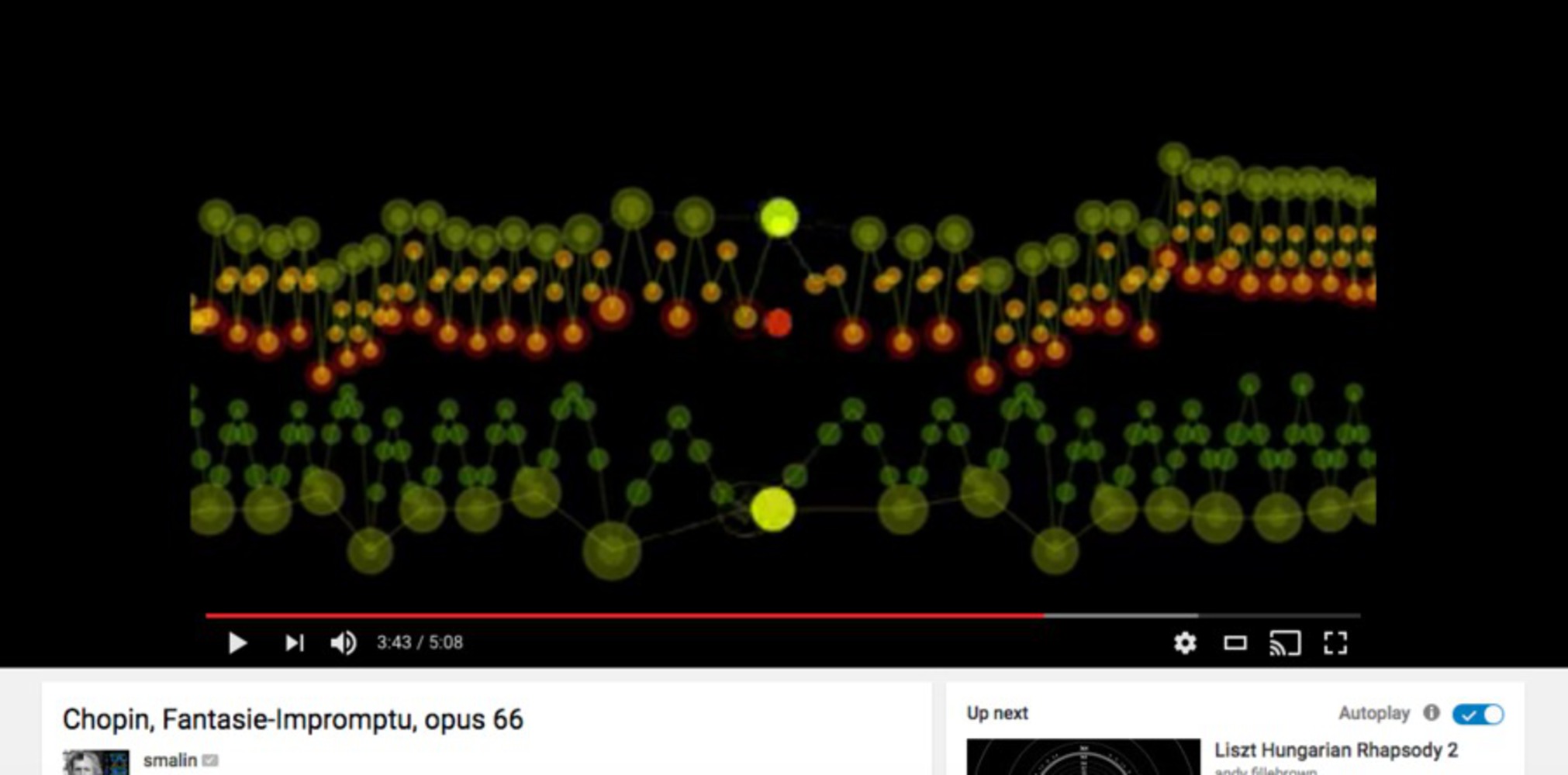

To create a visual translation mechanism, it was important for me to understand how music influenced Klee’s painting. One view is that music is the main component that influences visual outcome, such that the visual is more like residue from the experienced audible. In this system, creation concentrates around the suscitation of sound combination, and the visual stemming from it falls to a secondary standing. “Sound is not an arbitrary signifier" denoting another substance. Jim Drobnik alleges that “representation and interpretation are issues in which sound shares with pictures, yet sound reconfigures these very issues by inflecting representation with affect, and interpretation with embodiment,” challenging the conventions of visual models. “Signifying through its own materiality,” sound is substantive in itself and the visual merely produces a "transfiguration of an already perceived form.". The music-visual relationship can also be understood in a way that the visual is constructed to match and convey the audio, amplifying it through a different medium. When Klee became a teacher at the Bauhaus, he also became an “interpreter of signs.” Klee envisioned an art which translated the musical achievements of Bach and Mozart into visual terms. Ultimately for my project, I operate on the assumption that Klee visualizes sounds with the purpose that the "auditive cements the visual.”

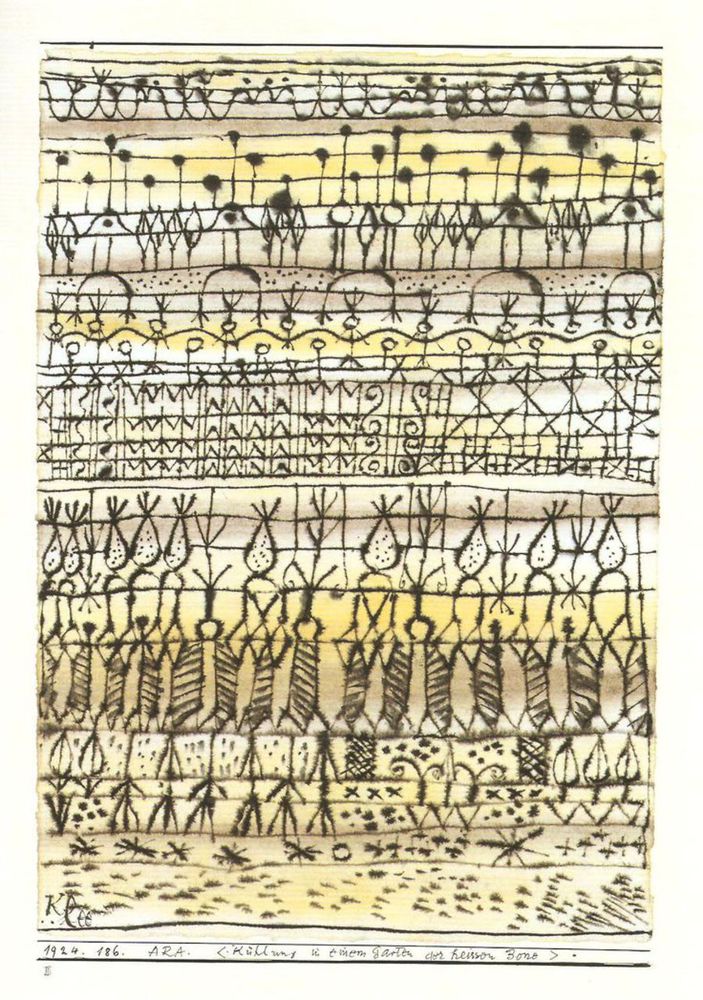

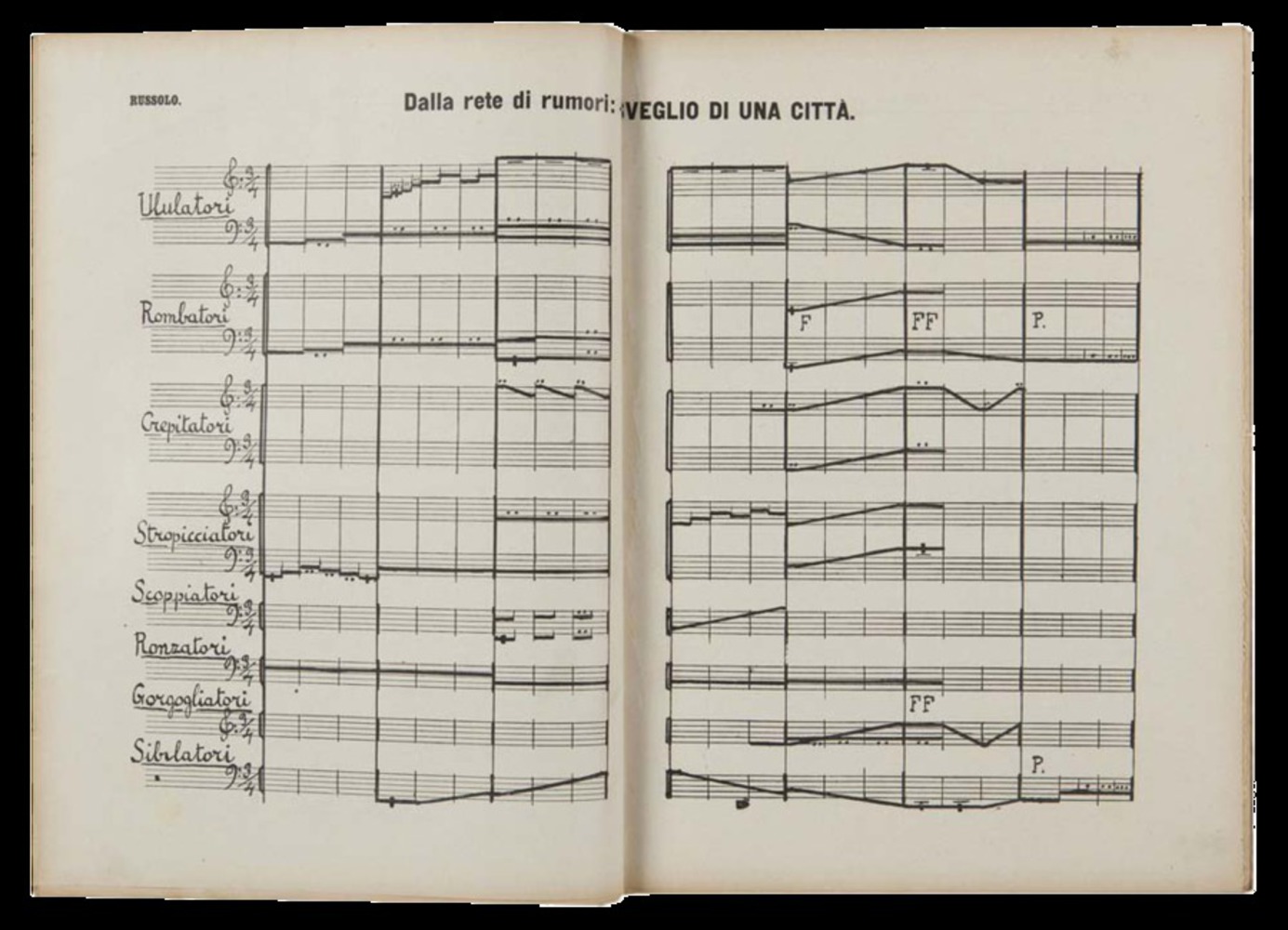

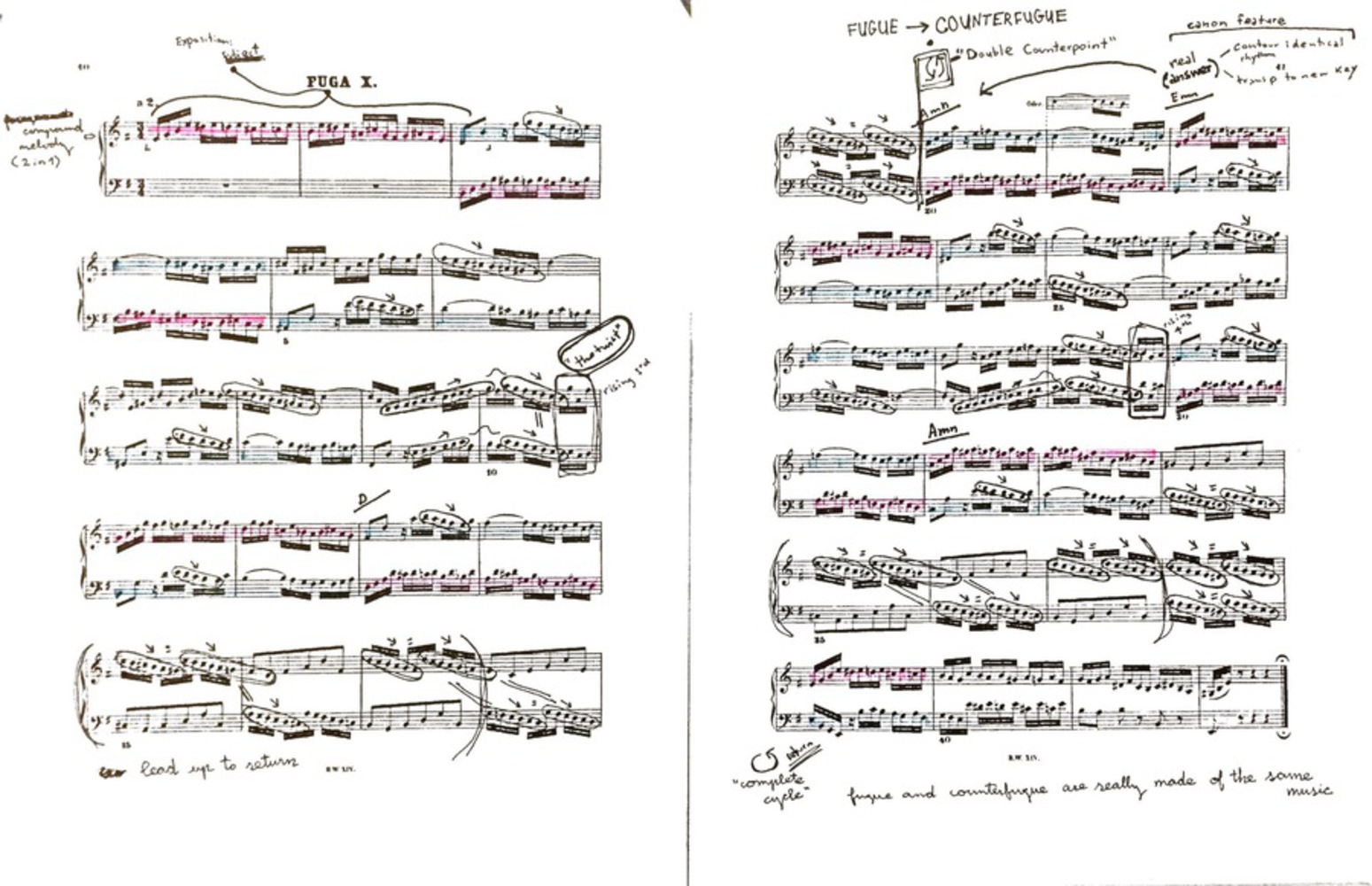

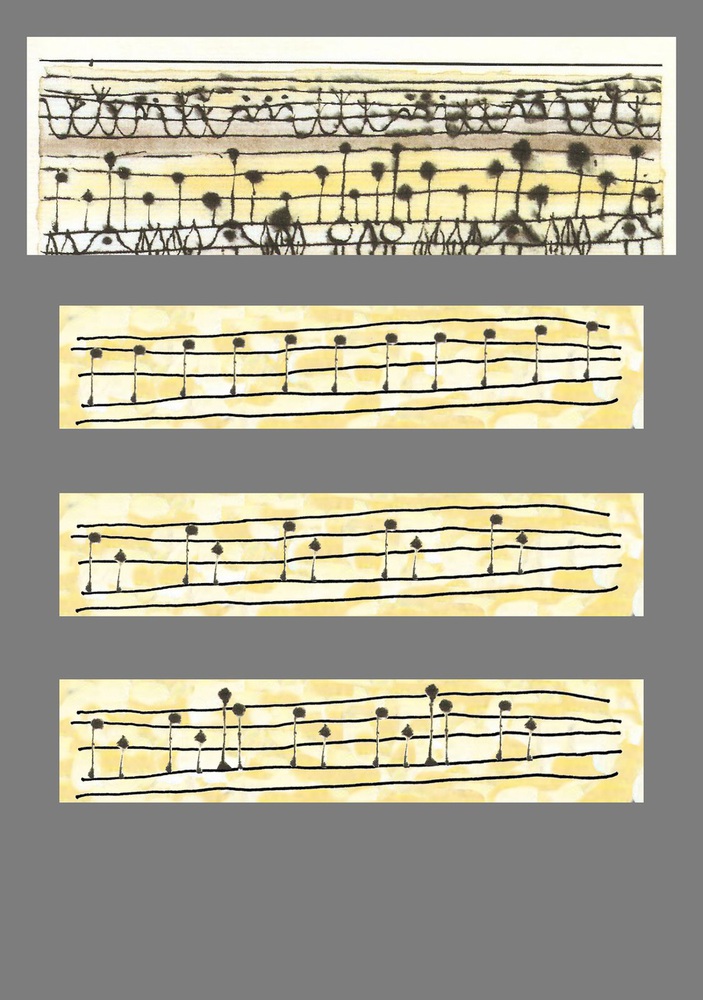

Klee endeavored to convert music into painting and my visual translation mechanism strives to reimagine this translation process. Many of Klee’s lecture notes to Bauhaus students contain musical notations and explanations of the mathematical approach to musical patterns. Before beginning any construction of my own, I looked at some of Klee’s music inspired paintings, focusing on the re-representation of rhythm, as this was a parallel already brought to my attention from research. The works that came up were Fugue in Red, In the Style of Bach, Polyphony, and Cooling in the Garden of the Torrid Zone.

Fugue in Red, based on Mozart’s Fugue in G minor, is a 1921 watercolor focusing on polyphony and counterpoint. "Klee perceived a clear visual connection to the structural articulations found in music. He connects structural articulations, exposing figurative forms or abstract derivations." Georg Predota offers a great analysis:

“Overlapping shapes float over a two-dimensional surface, with the temporal aspect graphically represented by a gradual shift in color. Moving from the dark background to maximum transparency, the visualized counterpoint combines in a cosmic harmony that reaches towards a new sense of spirituality. Although essentially structural in approach, this painting embodies Klee’s believe in 'harmony, autonomy, and universality in humankind.' As a musician and a painter, Klee essentially created a harmonious arrangement that echoes a universal order.”