Suppose a family lost their house and most of their earthly possessions in a flood, and the daughter's favorite teddy bear was destroyed. With the advent of laser scanning, 3D printing, and other customizable maker-type mediums, we could have a future where we would be able to recreate the daughter's exact teddy bear, giving her a small piece of comfort during this scary time. This technology could help children suffering from hospitals far from home, an elderly woman who lost her marriage ring of 35 years, etc. - with the objects we create, we could be giving back their memories as well. However, at what point is a recreated object a suitable replacement for the original? By getting an exact replica of the original priceless memory, does the new object take on the memories of the old, or does it simply stay a replica? This critical maker project takes the first step in provoking these questions.

Outcome

In the beginning of this project, I examined two relevant case studies to gain some insight into 1) what are the types of objects that people generally find memorable - are they unique or are they a mass produced object that has gained a special memory 2) how do the people react when their damaged and destroyed belongings are restored - is there happiness in getting the object back? or does it not feel like the same object anymore?

The Museum of Broken Relationships

In order to help answer the first question, I referenced The Museum of Broken Relationships, a traveling exhibit where people could donate items that are tokens of remembrance for a broken relationship, whether that because of a normal break up, a death, etc. The donated items were, as expected, a mix of very personal and unique items (such as a ceramic heart) and mass produced items that took on a special memory (such as a cheap dollar store frisbee). The fact that both of these types of items were donated to the museum poses an interesting challenge to my project, as for a very customized items I will probably not be able to recreate all the uniqueness of that item while mass produced items might not be personal enough to take on the weight of the original memory.

Hurricane Harvey Photo Restoration

The destruction caused by Hurricane Harvey has launched a similar effort as this project: volunteers partnered with Adobe to help families restore their water damaged photographs. Volunteers would go to afflicted houses and collect severely water damaged photographs, scan the photographs, use Adobe Illustrator to digitally fix them, and then print out and frame the new printed photographs. Although this project may display biased results (because Adobe used it for marketing), I do believe that many of the families did feel like their photograph was given back to them despite the physicality of the photograph being different. I think this stems from the concept that photographs are unique because of their content and image, not the actual paper upon which they are printed. Thus even though the paper changed, since the content was the same in this process, the families still felt like their photograph was restored to them. However, I'm not sure if this same emotional transfer will work for objects, especially those that are mass manufactured, as there is no necessarily unique content preserved in the physicality of the object.

After examining these case studies, I determined a suitable workflow for this project:

1) I would interview several of my friends about an important memento in their life that they have either lost over the years or left at home once they came to college. The important part of these interviews is that the person cannot have easy access to the memento, as I thought that might lead to a situation where they simply compare the accuracy of the recreation instead of focusing on the memory.

2) I would choose two friends' objects to recreate with digital fabrication techniques (including 3D printing, laser cutting, 3D scanning, etc.). The chosen friends would be unaware of my efforts to recreate their mementos.

3) I would have final interviews with those two friends where I show them their digitally recreated mementos and capture their feelings and expressions about the newly created objects.

Based on my research and intuition, I predicted that the digital recreations, no matter how close they might look to the actual object, would not transfer over the memories effectively; in other words, the new objects would be essentially junk instead of a memory.

Initial Interviews

In my initial interview stage of the project, I managed to interview six of my friends about on their important mementos and the memories behind them. Along the lines of my research with the Museum of Broken Relationships, the mementos ranged from the mass produced, such as a baseball glove, to the unique, such as a mug that was painted by a friend in grade school. I ended up choosing the two objects to recreate based on the strength of my friend's feelings about it; the two strongest feelings I perceived were that of Namrita Murali, who lost a pendant her mother had given her, and of Shivang Chordia, who describes his cricket bat that he shared growing up with his brothers. Their interviews are shown below.

After selecting Namrita and Shivang as the two people with whom I would proceed, I decided to tweak what I would attempt to represent. With Namrita, I would still attempt to recreate her pendant to the best of my ability, using digital fabrication techniques. However, with Shivang, I would not be able to recreate his cricket bat with any techniques I had access to; instead, I would attempt to make "a memento of a memento" and create an object that would allow him to remember his larger, personal memento of a cricket bat.

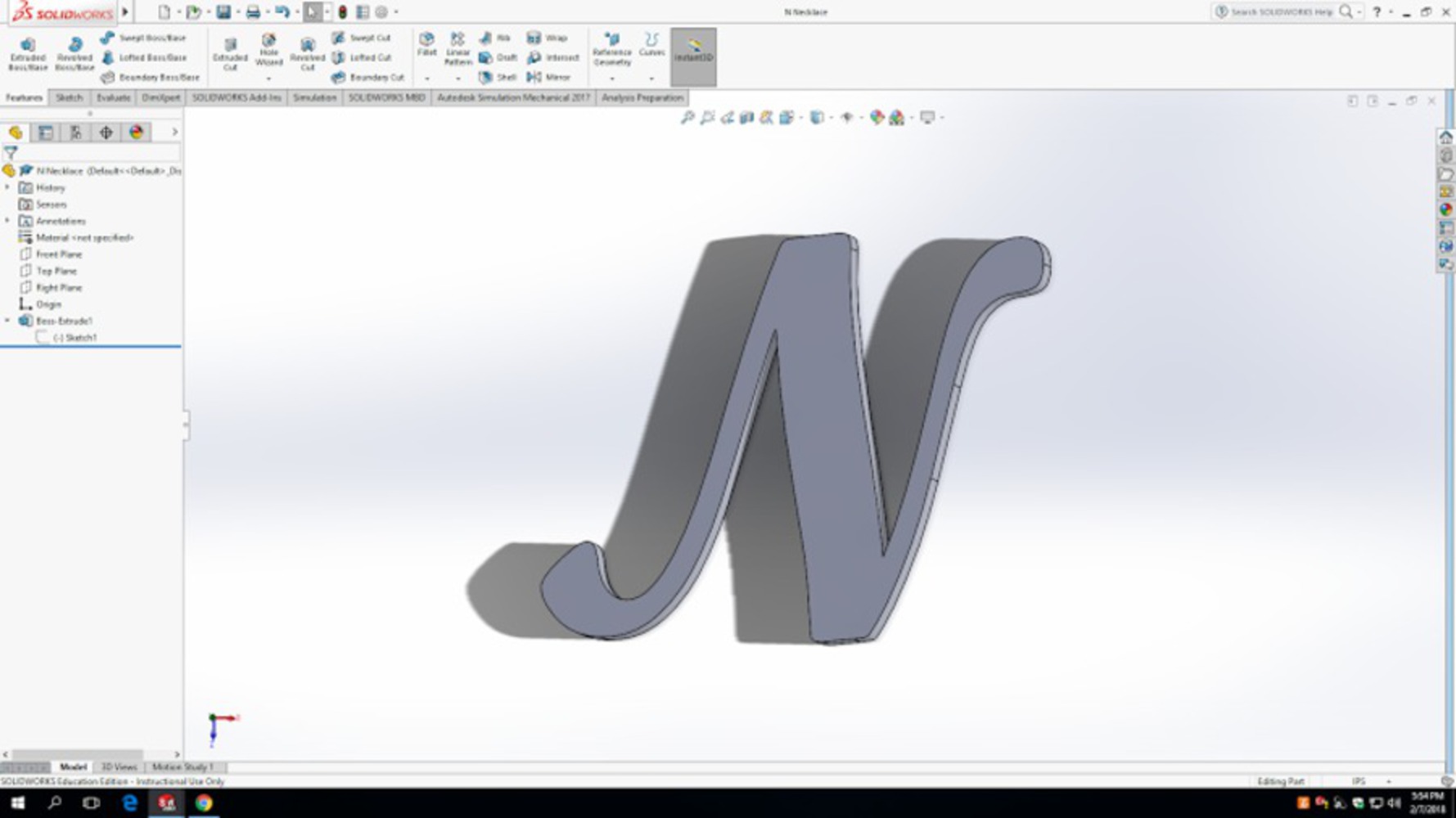

Recreating Namrita's "N" Pendant

As I mentioned above, for Namrita, I wanted to try to recreate her "N" pendant as closely as I could with my skill set and fabrication tools. Because the pendant itself was a planar letter, laser cutting the "N" seemed to be the most obvious fabrication method to use. The real challenge was identifying the aesthetic look of the "N." From her sketch of the pendant (shown below), I gleaned that the N had noticeable but not extreme flourishes, and that she had not necessarily drawn the flourishes in the right direction. I also guessed that perhaps the middle part of the N was thicker than the two side lines. Using these hypotheses, I created a CAD model of what the N would look like, and repeatedly lasercut the shape until I could get the smallest reliable size from the laser cutter, as I believed the N itself was relatively small (when comparing the size of the N to the clasp which attached it to the necklace). After lasercutting the final shape, I found a chain upon which to attach the N and made a new complete necklace to give to Namrita. I debated at one point whether to specifically buy a gold chain and paint the lasercut shape gold (as she distinctly describes the necklace as gold in the interview), but I felt that the necklace may look like gold but would definitely not feel like it, and thus it might be better to present it in the original material form. The transition and final form is shown below.

After finishing this process, I interviewed Namrita again, which is when I showed her the final form I created (which she was not aware I was going to make). Before the interview, I gave her a vague explanation of my project (an attempt to recreate important mementos), after which she immediately got visibly excited as she realized I recreated her necklace. The formal part of the interview is shown below. I was very surprised at how much she resonated with the object; she was noticeably appreciative of the necklace, mentioned that the curves of the N was exactly right, and that this object did remind her of that necklace which she lost. After this interview, she told me she was going to tell her mom about it and immediately took a picture of it and started talking to her.

This was a much stronger reaction to what I was expecting, as I did not expect her to really connect with the object at all (as it wasn't her actual necklace). She did mention that if this was to be a longer term project, then she would like to see more iterations to get the necklace exactly right, in which case that new object might take on all the memories of the old.

Creating a Memento for Shivang's Cricket Bat

As I mentioned before, for Shivang's memento of a cricket bat, I decided that instead of trying to recreate the bat I would make a "memento of the memento" to compare the reaction with the more exact recreation of Namrita's necklace. I had noticed in Shivang's interview that the cricket bat was mostly special to him as it reminded him of a shared experience with his brothers, and thus I knew whatever I created should in some way reflect that. I thought a possible way to do so was to create a keychain, something that a person could keep with themselves most of the time, of a cricket bat. The bat would also be adorned with their family's last name, Chordia, to create a sense of personalization and the word "Bros" to indicate the unity of them. Moreover, I made sure that I would create three of them, one for each of the three brothers so this keychain could be another shared object between them. My initial reaction was to actually 3D print a cricket bat with these adornments in order to have some of the physicality of the curve of the bat; however, after some experimentation, I found the curve was not being well preserved in the scale I was working. Therefore, I decided to focus on the texture of the wood instead, lasercutting the keychains out of a birch sheet.

With the bat keychains created, I went to interview Shivang again to show him the new mementos and see his reaction. I found his reaction to be more lukewarm, and I felt more motivated by the fact that I took the time to lasercut a realistic looking bat for him. The fact that there were three bats did seem to connect more to the original memory of the cricket bat, as he immediately knew it was for each brother and he did mention that these bats did actually create an attachment for him. However, he also mentioned that the bat itself would be much more powerful, because of the specific weight and feel of that bat that he came to know so well.

Reflections

This project altered some of my beliefs about the values of mementos; through this process, I found that even a somewhat close reproduction of a personal object (such as Namrita's pendant) was more effective than the "memento of a memento" approach I took with Shivang. In my ideal scenario, I would like to be able to check up with them in a month or so to see if they still kept the objects I created for them, if they held any place in their lives or were they forgotten after a short period. Additionally, in Namrita's case, I feel that the interaction might have been more powerful because it was an object that she actually lost (and never expected to see again), when in Shivang's case, it was an object that he could access once at home and could reasonable expect to see again; thus, in future work, I would like to try to experiment more with people who have objects that are actually gone from their lives and have no hope of seeing again, as I think that is when the interaction might be the most potent. Additionally, although for this experiment I thought it would be better to not tell Namrita or Shivang about the next steps of the project, in the future, I would like to try a more open approach with the people knowing that I would be attempting to recreate their object or with maybe even people approaching me to recreate their lost object. I would also like to see how this experience might work with people who are not so close to me, as I think my friends may have been affected by the fact that I made something for them on my behalf rather than a complete stranger. Along the similar lines, I would be interested to see how this might work in a museum or workshop type of environment, where people actively approach the recreation team to try to get a facsimile of their object back.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Namrita Murali, Shivang Chordia, Morgan Dively, Joseph Paetz, Tushita Gupta, and Gaurav Lahiry for their participation as the subjects of this project. I would also like to thank Prof. Daragah Byrne and Wei-Wei Chi for their help in providing critique as the project developed.

You can upload files of up to 20MB using this form.