Think piece:

How They Perceive Us

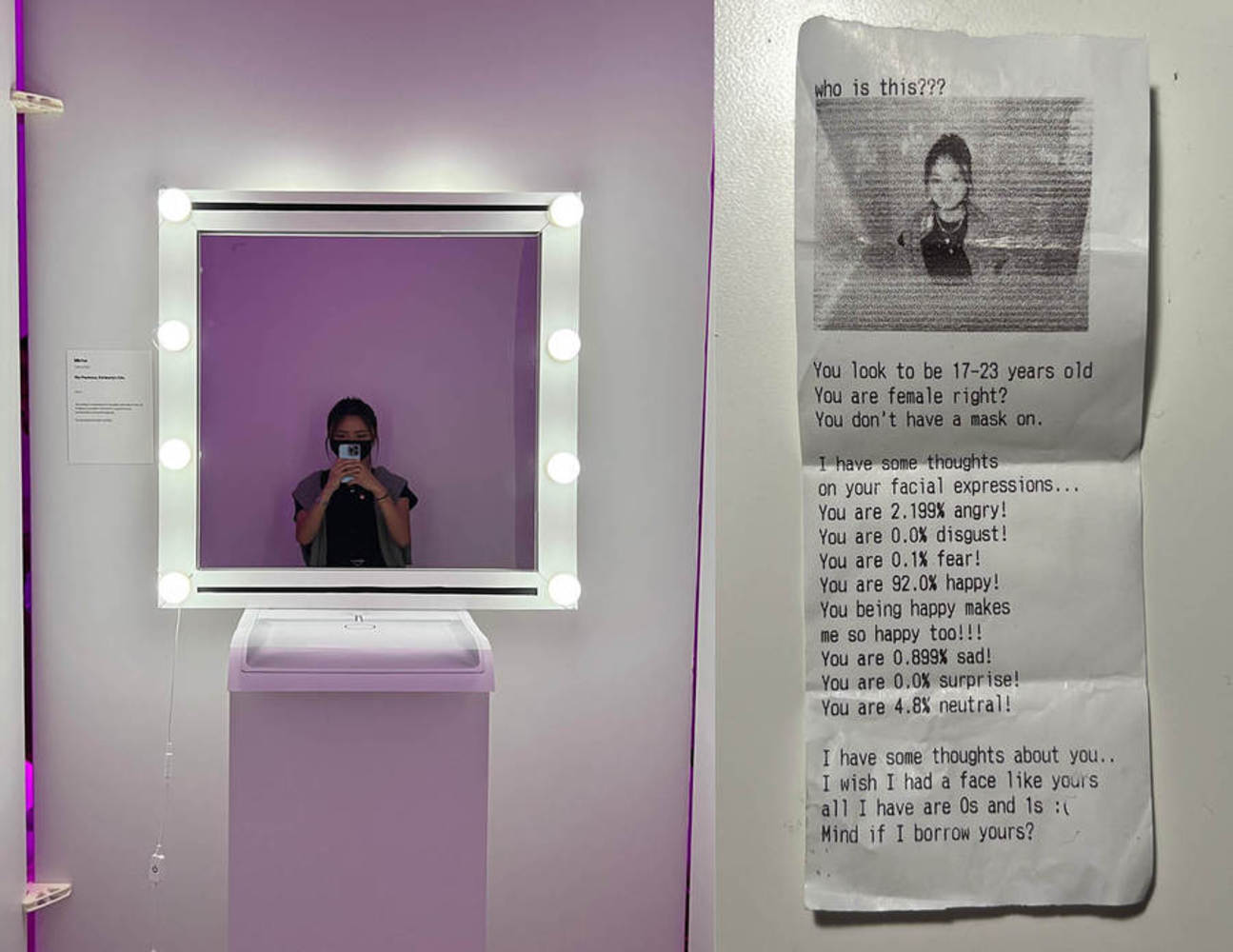

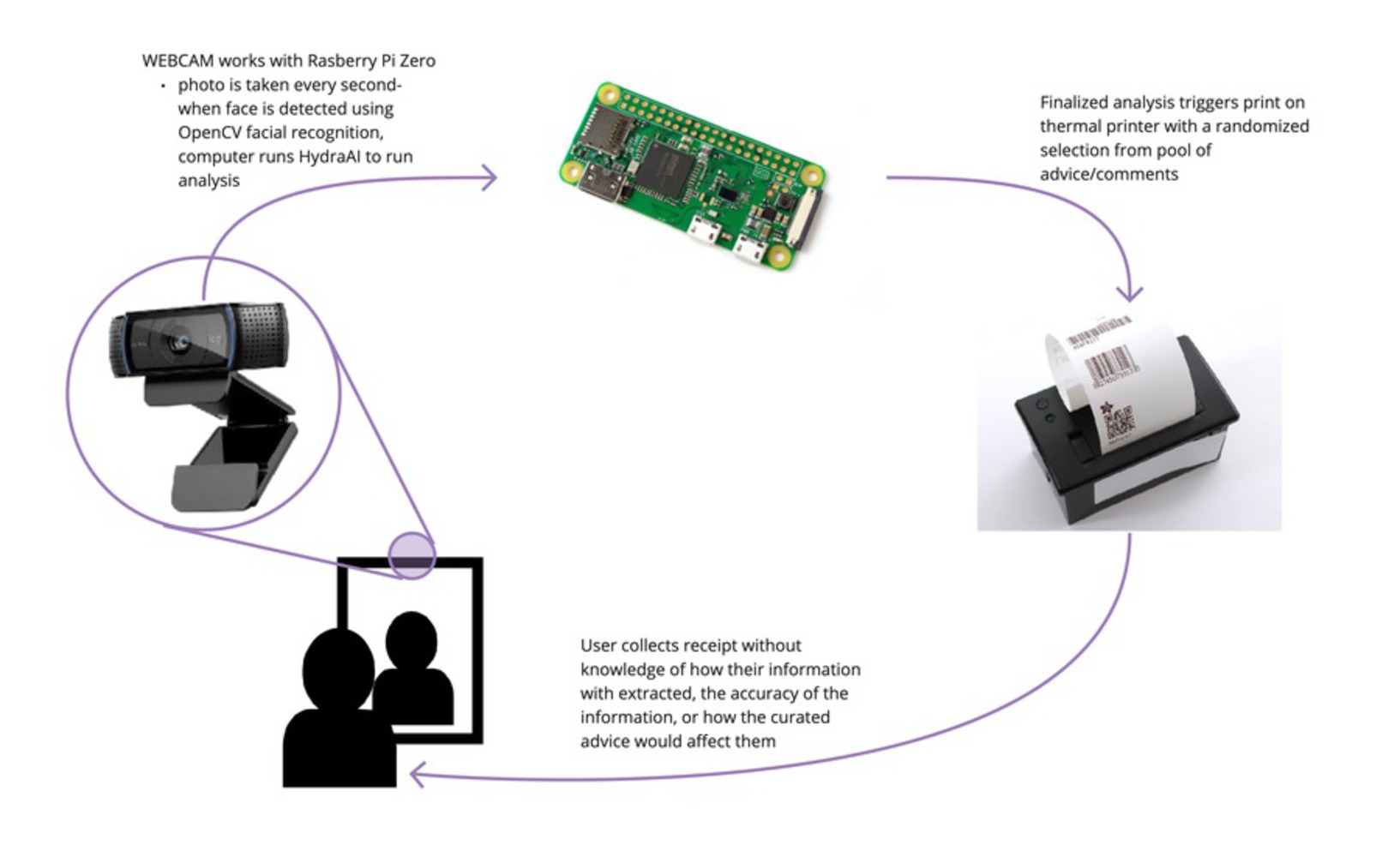

When it comes to the internet and our smart home devices, “consent” is a vague umbrella term that is often compromised for the benefit of convenience and intelligence. Our everyday interactions with our devices seem harmless to us until they’ve learned so much about us that they can infer, or even control, our next move. Algorithms are designed to incentivize this interaction, through targeted ads and suggestions to personalize one’s experience .This data collection is a spooky fact behind our devices that everyone knows- is knowledge the same as consent? So, how are our devices collecting our personal data, what exactly can our devices find out about us, and ultimately, how do our devices perceive us?

With the pervasiveness of technology and the increasing dependence on our devices, people are losing the distinction between the digital realm and the physical world- especially when our digital realm is personalized and smart. The first tactic our devices use to keep us engaged is in the psychological stimuli we receive from our devices. Algorithms utilize these psychological leverages to encourage interaction with our devices in order to collect, store, and manipulate our personal data. The separation anxiety many adults face with their devices is the result of a dopamine-driven reward circuitry, which companies will use to keep them online. “Adults in the US spend an average of 2-4 hours per day tapping, typing, and swiping on their devices—that adds up to over 2,600 daily touches” [1]. Within the interactions, personal data is collected using features such as autofill, cookies, and search history. Large platforms such as Facebook and Google may even know users better than they do themselves.

Our digital profiles not only consist of basic information, but it also includes our preferences, opinions, habits, and many more characteristics we may never have even thought of ourselves [2]. “Last year Google amended its privacy policy so that data from its DoubleClick ad network could be merged with the other data it knows about you—like your name and your favorite YouTube channels—to build up a very comprehensive picture of you and your tastes” [4]. Not every company has the reach of Google or Facebook, but data can be easily bought and sold between firms specializing in this kind of profiling. In 2018, a reporter from Vice conducted an experiment to see how our smartphones use its monitoring equipment like its mic and camera to absorb audio and videos without distinct consent. The journalist spoke preselected phrases twice a day for five days in a row while monitoring his Facebook. Sure enough, when he used the phrase “back to university”, he saw ads for summer courses. And when he changed his phrase to “cheap shirts”, he quickly saw advertisements on his Facebook feed for low-cost apparel [5]. Data collection occurs even when we’re not interacting with our device, furthering the assimilation of the digital realm and physical world.

When buying, interacting with, or neglecting our devices, we have the right to understand the extent of which our information is being collected and used. A great weight of spooky technology comes from its abstractness and intangibility. However, as new devices and softwares enter the market at alarming rates, have we lost the timing to detach and analyze it? New technology is not only an opportunity for the future, but an opportunity to reflect on the past and present. As technology continues to advance to greater heights, it has become ever so important to understand the ethical decisions of machine learning and its applications in consumer devices.

References: