Artist

Among the abstract expressionists of the 1940s is the artist Willem De Kooning. When we think of abstract expressionism, we may think of Jackson Pollock’s pieces, where he splashes oil paints on canvas to create a bloom of dynamic colors. Unlike his fellow contemporaries of Jackson Pollock, Franz Kine, Mark Rothko, and Clyfford Still, much of De Kooning’s works portray a central form, yet the way he draws, using brush strokes, charcoal, or—later in life—clay, retains as much expression and movement as other artists’ works without losing the subject of his piece. Whereas other abstract expressionists lean toward the “abstract” side of the movement, De Kooning leans toward the “expressionist” side.

For De Kooning, fine art is a passion rather than a communication of ideas. He has said, “I don’t paint with ideas of art in mind. I see something that excites me. It becomes my content” (The Art Story). Yet, the most recognized of De Kooning’s pieces are what critics considered the most offensive. While he had not intended his pieces to be interpreted in such provocative ways, in doing so, he gained a reputation as a member of the abstract expressionist movement.

Work

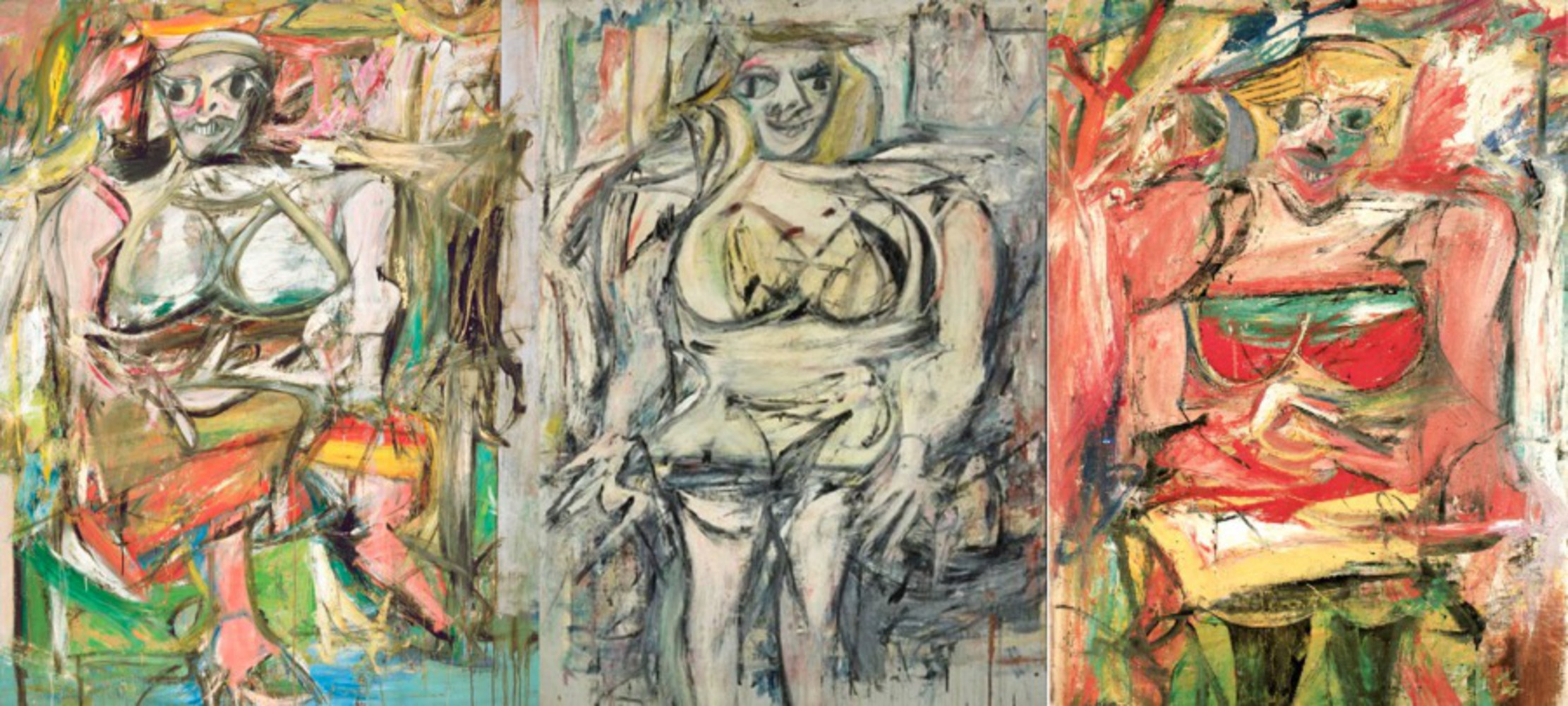

De Kooning is most widely known for his Woman series of paintings—a series of oils on canvases depicting an abstracted feminine form. In each painting, a swirl of brush strokes and colors manifest into a woman-like shape that fills the center of the canvas. De Kooning crafts the lines in each piece so the form is evident but ambiguous with the piece’s background. The colors behave similarly; we have splashes of red on the skirt of a woman, but we also have the same red in the background, seemingly not representing any particular setting.

Despite depicting a central form, De Kooning does not follow traditional compositional rules. Not only does the woman in each piece fit squarely on the canvas, but also we do not see technically accurate proportion or perspective. Critics have called his pieces “violent” and “daring”. A less acerbic word that later art historians use is “figurative”, and we see this evidently. De Kooning was inspired by cubism, so the women’s forms in each painting are flattened and simplified. Lines intentionally mingle with each other to lessen the distinction between form and background, and, in addition, show the expression intended in the piece.