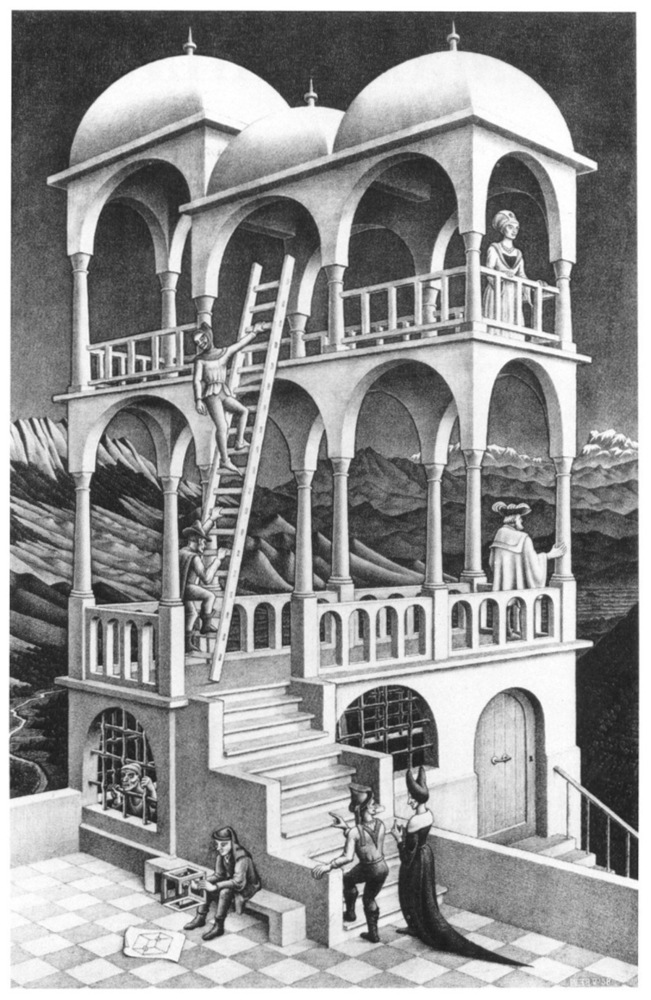

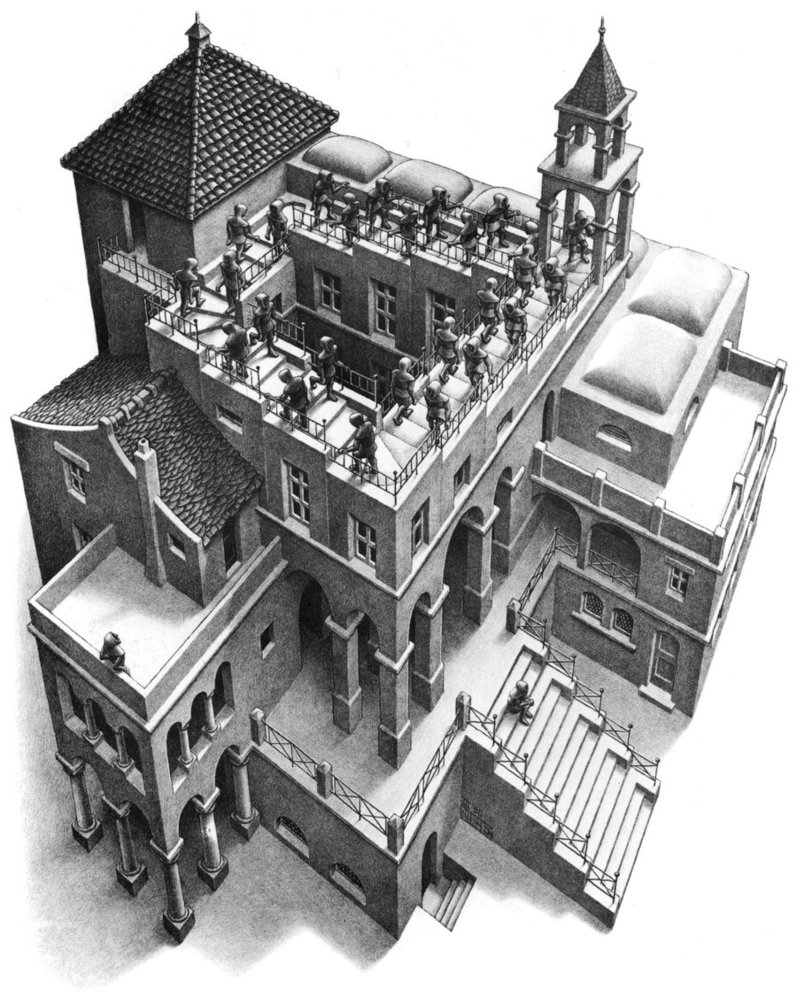

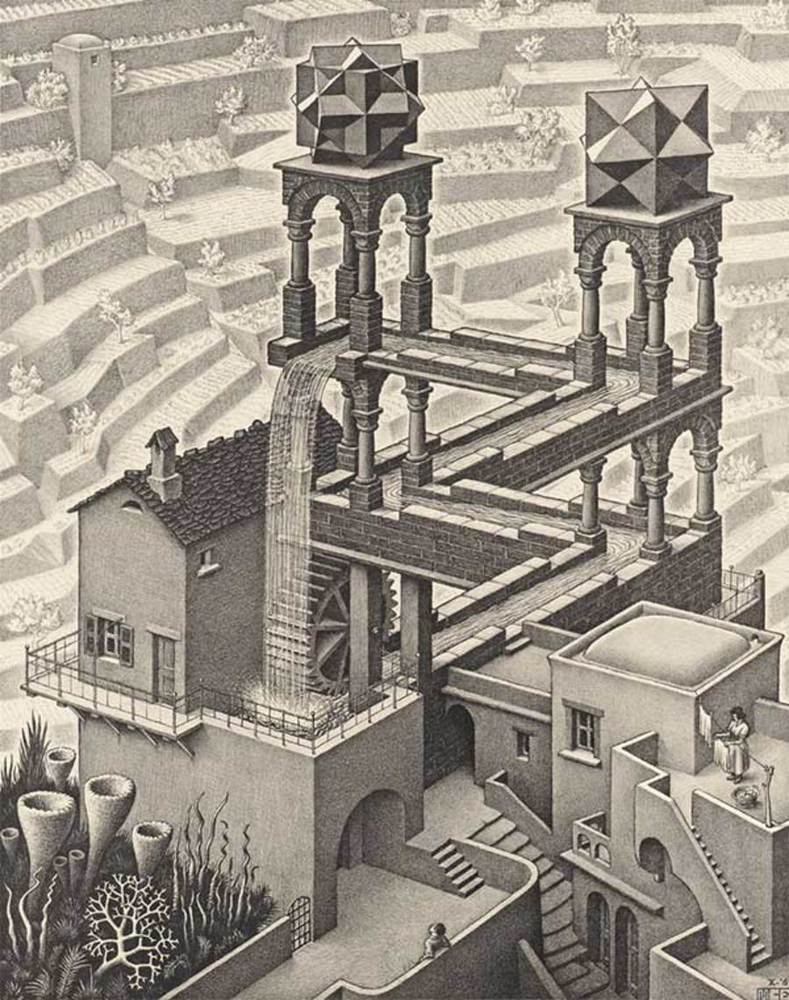

Ah, optical illusions. Since middle school, this subject has been a favorite of mine. I had always considered optical illusions an amazing synthesis of science and art, I have never found a more impressive artist than M.C. Escher (Can you imagine that his works are lithographs?), and I have yet to tire of the subject! I could say much about the many optical illusions people may be familiar with, but I will focus on those that use parallel perspectives to create impossibilities. I cannot explicate its mechanisms fully, but I hope to demonstrate its gist through examples.

Perceptual Illusion

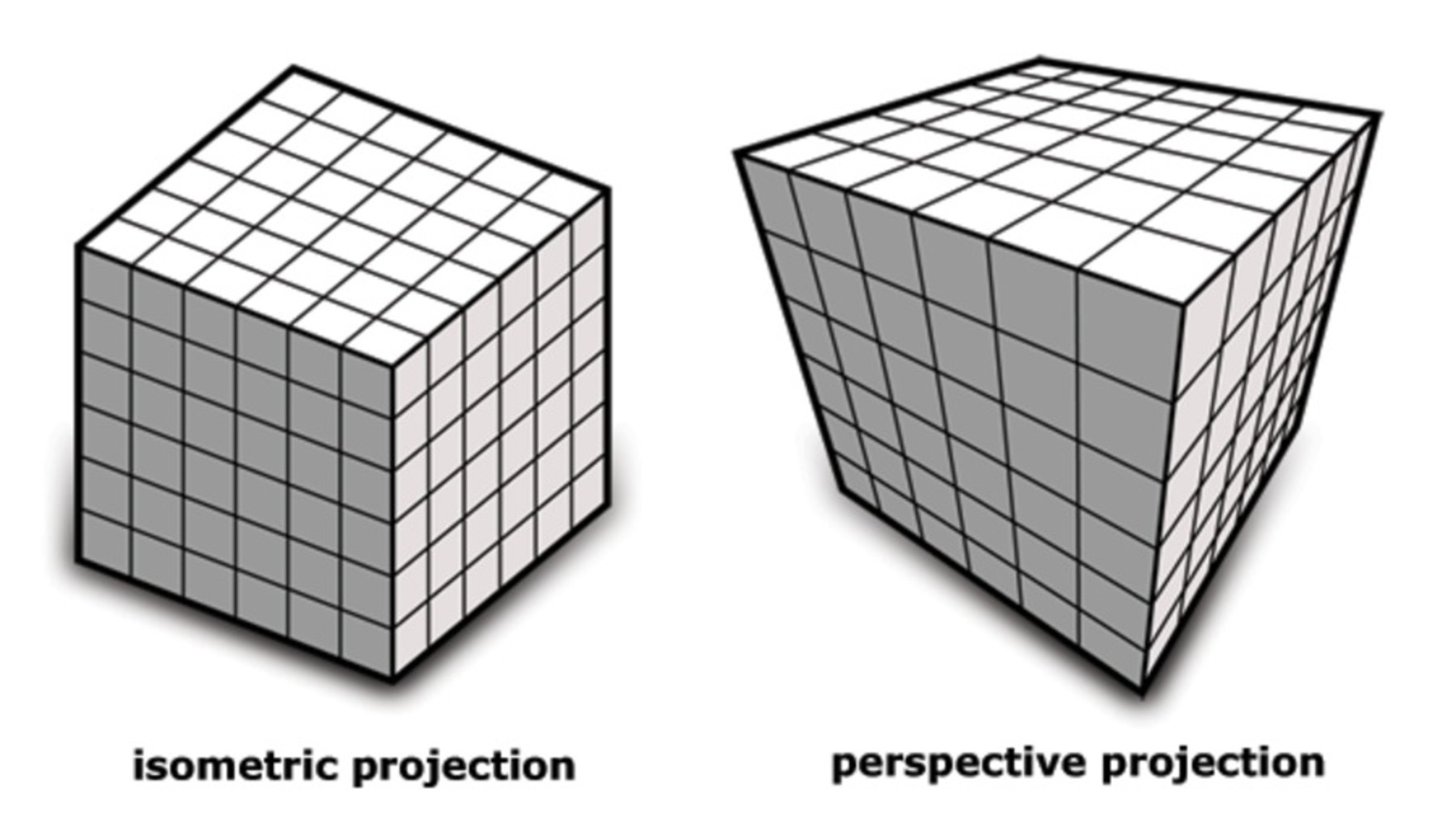

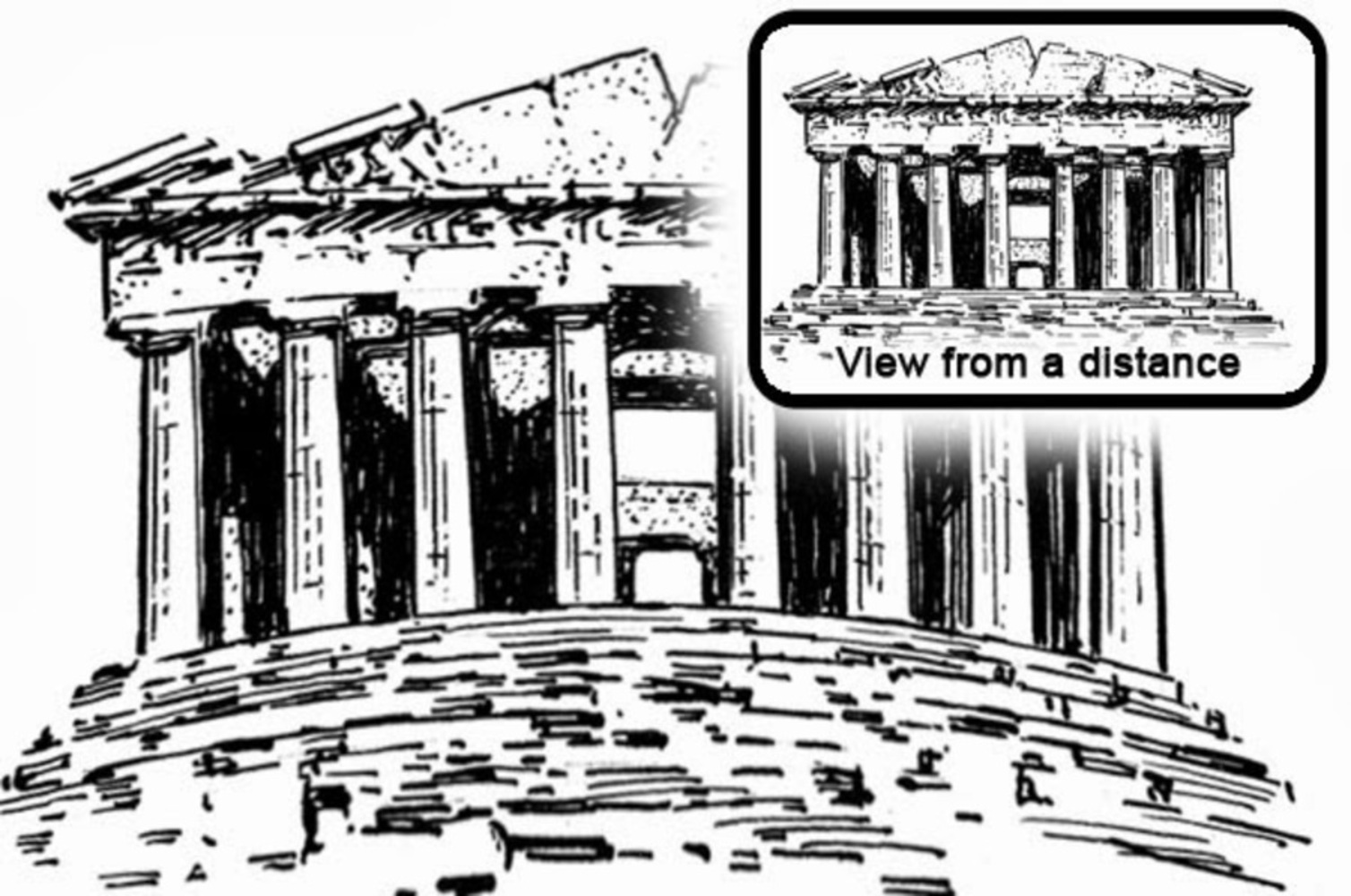

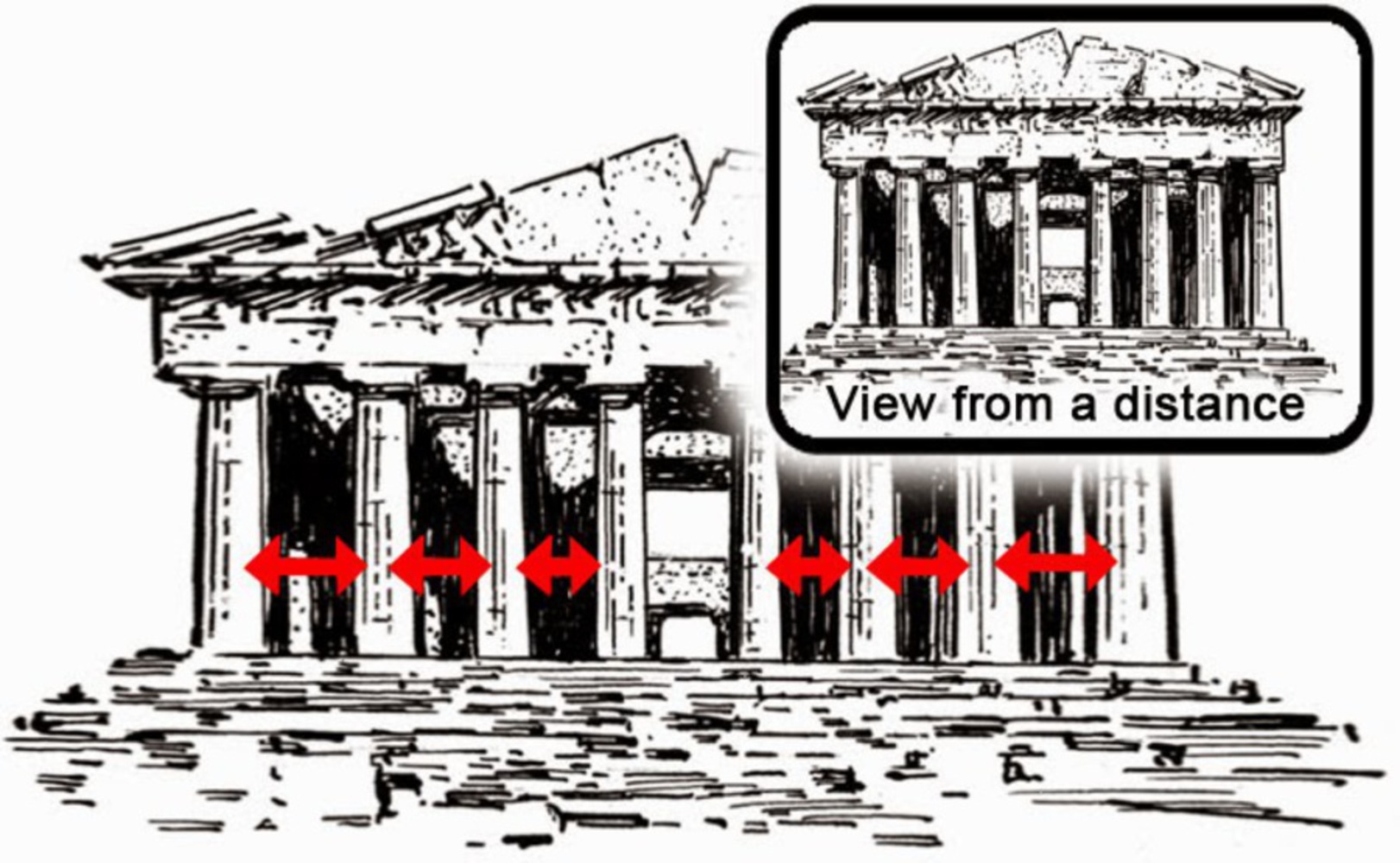

Parallel projection is a typically used graphical projection used typically for depicting schematics and other images of a mechanical nature. In a parallel projection, there is no adjustment for depth, so all objects appear to have the same relative size and distance. In technical design, this is convenient, since all units are accurate and there is no adjustment for scale required. For the layman, as well, this method of projection seems to make sense. Even if it lacks true depth, people can cognate the illusion of depth easily.